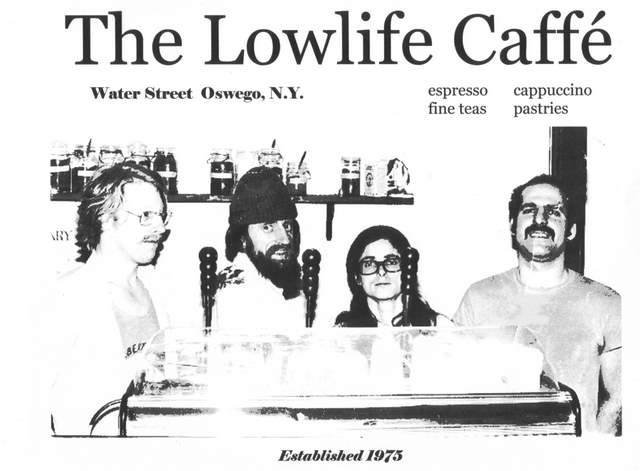

I’m pleased to offer you my second column on the history of the Ontario Center for Performing Arts, a popular setting for live entertainment in the city of Oswego. My last column covered the very early years of the Oswego Music Hall, as it was originally known, beginning with a coffeehouse called the Lowlife Caffe. Founded by Dick and Sue Reinert, the Caffe was a springboard for what Dick had in mind for Oswego.

“Dick Reinert was the catalyst for the Music Hall,” recalled Paul Maggio, who spent lots of time there, both as part of the audience and as a performance artist. “Dick had seen things like Shakespeare in the Park in New York City and he wanted to bring in culture to Oswego.”

One of Dick’s children, Joe, shared some thoughts about his dad’s desire to establish the Music Hall: “In his soul, my father wanted to be an artist, but he was also aware that he couldn’t make money doing that, so he followed a career in the sciences. Still, he wanted to be close to artists who were creating and I think the Music Hall was a way for him to do that.”

Old City Hall, where the Music Hall began, was located on Water Street, and with its abandoned warehouses it didn’t seem like a welcoming place for performances. But Dick started bringing in quality performers to that questionable space and he wasn’t only interested in folksingers and bands. He also brought in poets and theatre groups, including one created by Donna Inglima, who’d moved to Oswego from New York City, where she had studied acting.

“I worked at a store in Oswego,” Donna said. “One day, Dick came in and asked me what I did beyond that job. I told him I was a theatre person and he said, ‘I run the Music Hall. Why don’t you come and do plays with us?’”

That conversation led to Donna founding the children’s theatre troupe Animal Crackers Unlimited. After brainstorming with other Oswego-based actors, including Fullis Conroy, Seth Cutler, Paul Maggio and Steven Schwartz, Donna started staging plays, which were often based on fairy tales, in Old City Hall. She described the Hall’s setting for the troupe’s performances:

“Originally, it was where they built ships and its wooden structure and big windows made it feel so commanding…but it was also funky and there was a warmth to it. Chairs were in short supply, so we saved them for adults and found carpet squares at a local rug store for children. They would sit on the floor close to the stage.”

Animal Crackers’ plays were scheduled in between Dick’s musical artists and Paul Maggio remembered the preshow work that had to happen before the troupe could perform. “Our shows were often on Saturday morning and we actors would come in to get ready. Part of what we had to do was clean up from the night before—clean tables, pick up bottles and such.”

By the time the Reinerts left Oswego in early 1980s, the Music Hall had established a following, with some of those who’d enjoyed the performances stepping up to keep them going. One of the first new leaders was Allen Belkin, who explained the many responsibilities of a Music Hall manager.

“I identified and contacted performers and scheduled shows. To publicize events, I wrote press releases and public service announcements, recorded radio commercials, and created a monthly flyer and posters to hang up around town. I arranged hospitality for performers and made sure the room was set up for the show. I recruited and coordinated the many volunteers who helped.”

Among those volunteers was Catherine Cerulli—longtime Music Hall attendees may remember her as Cathy Barbano—and, as she explained, “I started out like many Music Hall volunteers did, as an usher: welcoming people at the door, showing them to their tables. From there, I became part of the board of directors, which was a pretty informal organization at first.”

Those informalities included the Music Halls’ finances. “It was operating on a shoestring budget,” Catherine said. “I worried that we wouldn’t make enough money from ticket sales to pay the artists—and that was back when even a well-known singer was only getting $150 or $200. Sometimes I’d bring cash from home in case I had to make up the difference.”

According to Catherine, the original board of directors learned by trial and error. “Everything we did we did as a group. Fliers to advertise our shows were literally cut and pasted before they could be printed. We’d get together at someone’s house—most of us were parents of young children—and we’d fold fliers, tape them closed and handwrite addresses.”

Eventually the Music Hall board developed strategies to supplement performance revenue. “I learned how to write grants,” Catherine explained. “We started a membership program and began reaching out to other coffeehouses and area schools around Upstate New York to see if we could coordinate booking artists.”

Over the years, Music Hall audiences have enjoyed quality performers because those who booked the shows have always looked for more than talent; performers have to connect with the audience, too. Artists noticed how playing at the Music Hall was a unique experience. Folksinger Mark Rust explained why:

“What I remember about playing [there] was that it was like playing a small concert. Most of the other venues I played in were smaller coffeehouses, kind of like oversized living rooms, with not always the best sound systems. What also stood out for me was the strong community support for the Music Hall. Many places I play are organized by one person or maybe two or three. But the Music Hall has this strong group of volunteers who are there to make sure the audience gets the best performance and that I had everything I needed to give that performance.”

Eventually the Music Hall moved from Water Street to the New Covenant Church on Oswego’s east side, and then, in 1987, to its present location at the McCrobie Building overlooking Lake Ontario. And no matter where it’s provided performances, those on stage, in the audience or on the volunteer staff keep talking about the sense of community inherent in the Music Hall.

Here’s how Michael Moss, who is the current volunteer coordinator, explained a key element to that sense of community. “Without the volunteers,” Michael said, “there would be no Music Hall.” Linda Knowles, who also organized volunteers for many years, agreed. "Volunteers are the heart of the Music Hall. Help from every member of a family, no matter how young or old, is valued. I remember children filling popcorn baskets while their parents set up tables and chairs before a show. At the end of the night, members of the audience would spontaneously rise to help break down the stage and all that had been set up. Though everything was folded and put away, an air of gratitude, of a job well done, remained."

Maybe all these references to volunteerism and community-building wouldn’t have seemed so unusual 50 or 60 years ago, but today, with our fragmented and divisive world, knowing the Music Hall still functions as a community feels like a vital breath of fresh air. More than forty-five years after Dick Reinert created a space where people come together for music and performance, it’s the coming together that people most remember.

Singer and musician Mark Rust is one of the many performers who’ve shared their talents in the forty-five years since the Oswego Music Hall was founded.